The Wallace Journey in NF Research

Margaret “Peggy” Wallace, PhD, Professor, University of Florida

Discover more articles in the Women in NF series by clicking here.

A foreword about this essay: Although I’ve had amazing male mentors over the years, for the purposes of this initiative, I am only mentioning the women I’ve especially looked up to over the past 36 years, although I’m sure I’m missing some.

My introduction to NF1 was in my PhD program in the early 1980s, through a 4-year-old boy whose family came from Saudi Arabia to our department’s genetics clinic. The boy had a huge tumor involving his neck/throat area. The diagnosis of NF1 was made, but of course, there were no solutions to offer for this inoperable plexiform. It was pretty clear that the tumor was going to kill this boy before long, a very sad, sobering situation. When I was offered a postdoctoral position to work on NF1 at the University of Michigan, using the new positional cloning technology, I was happy to accept, hoping that this research might ultimately contribute to therapies for severely-affected patients. At that point, little was known about NF1, other than an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, recent linkage to chromosome 17, and publications describing/ analyzing the clinical features such as from James Neel, Frank Crowe, and Vic Riccardi. There appeared to be different types of neurofibromatosis, but this was murky because of variable clinical features. There were no therapies other than surgery to remove/debulk tumors, which were not very successful except for cutaneous tumors. And, of course, there were no sources of information available outside of libraries (pre-internet), and most physicians knew nothing about NF. Unfortunately, at that time, NF was also associated with “The Elephant Man,” Joseph Merrick of England, who was seriously disfigured and disabled with what we now believe was Proteus syndrome. It took years to come to that conclusion and try to break that connection, which unfortunately still sometimes comes up.

University of Michigan NF1 Cloning Team 1990

During my postdoctoral years (1987-1991), I learned a great deal about NF1 (diagnostic criteria defined during that time), positional cloning approaches, rising technologies (PCR was brand new!), and gaining experience working in a team. In addition to lab work, I also had opportunities to meet NF1 patients in clinics and at events held by the Michigan National Neurofibromatosis Foundation (NNFF) chapter. I also was fortunate to receive a Young Investigator award from the NNFF and started attending its research meetings (today’s NF Conference), which had begun convening in recent years. The first couple, in New York, only had 30-50 people in the room from the US and Europe, including women PhDs I viewed as role models – Karen Stephens, Nancy Ratner, and Meena Upadhyaya. I was impressed by the camaraderie of the group, and how a nonprofit foundation was taking the lead to move the science forward, a very difficult task, but driven by conviction and a common cause which was foremost at these meetings. By the end of those four years, the study of NF1 had started mushrooming, having emerged from the bottleneck of finding the gene and having clarity on clinical diagnosis. These gains also starting opening opportunities for NF research funding from other sources, such as government agencies. To accommodate this growth in the NF field, the NF research meetings evolved and moved to Junes in the Hotel Jerome in Aspen, Colorado. In that secluded environment, participants were able to immerse themselves in all things NF, sharing pre-published data and establishing collaborations.

I began my faculty position at the University of Florida in 1991, fortunate to bring some of the NF1 project with me. Immediately I began establishing collaborations and recruiting patients/families into my studies, in part through the Florida Chapter of the NNFF. By 1995, the previous NF knowledge and interest “bloom” looked trivial, with the exploding emergence of email, animal models, new lab methodologies, internet, early genomics data, and NF books/chapters/journal publications. Not to mention cloning of the NF2 gene. Concomitantly, awareness about NF in the medical community grew, although there were still no treatment improvements. But there was a growing realization that a separate condition was in the mix as well: schwannomatosis.

Dr. Wallace at Florida NNFF meeting, 1990s

In the two decades after that, there was steady growth in all areas of NF, in part related to the US Department of Defense beginning its Neurofibromatosis Research Program, which funded the first NF clinical trials and larger scientific studies, continuing to today. The NNFF grew its YIA program, helped with annual lobbying to retain the DOD NF Research Program, and moved the NF meeting out of Aspen to accommodate the growth in attendees. Other important events included the NNFF hiring its first Chief Scientific Officer, Kim Hunter-Schaedle, PhD, in the mid-2000s to help the foundation move toward the future, both in steering research as well as awareness and education. I remember when the NNFF Board of Directors realized that its fundraising had hit a budget ceiling that was insufficient for planned initiatives and chose to change its name to The Children’s Tumor Foundation (tagline: Ending Neurofibromatosis Through Research) to increase donations from people who knew nothing about NF or could even pronounce the word. Although this alienated a. small percentage of members, it was successful in growing the CTF budget to where it could fund different kinds of small studies, including pilot pre-clinical/translational work in all types of NF. And continued YIA awards, too, as a support for basic science; I continued to help with this program as the Chair of the Research Advisory Board for over 10 years. I also enjoyed helping mentor young scientists in my lab and through the CTF over the years, some of whom have remained in NF research (or have become doctors and are knowledgeable when they see NF patients). A role model throughout my involvement with NNFF/CTF was Suzanne Earle, a Florida businesswoman whose daughter had NF2. She joined the NNFF Florida Chapter Board of Directors in the late 1990s, where she became chapter President in 2001. Her leadership abilities were such that she quickly became involved nationally, rising to the top – Chair of the CTF Board of Directors by 2006. She continued to serve with the CTF until just a few years ago, a steady influence of reason and consensus-building, ensuring that we don’t lose sight of the primary goal.

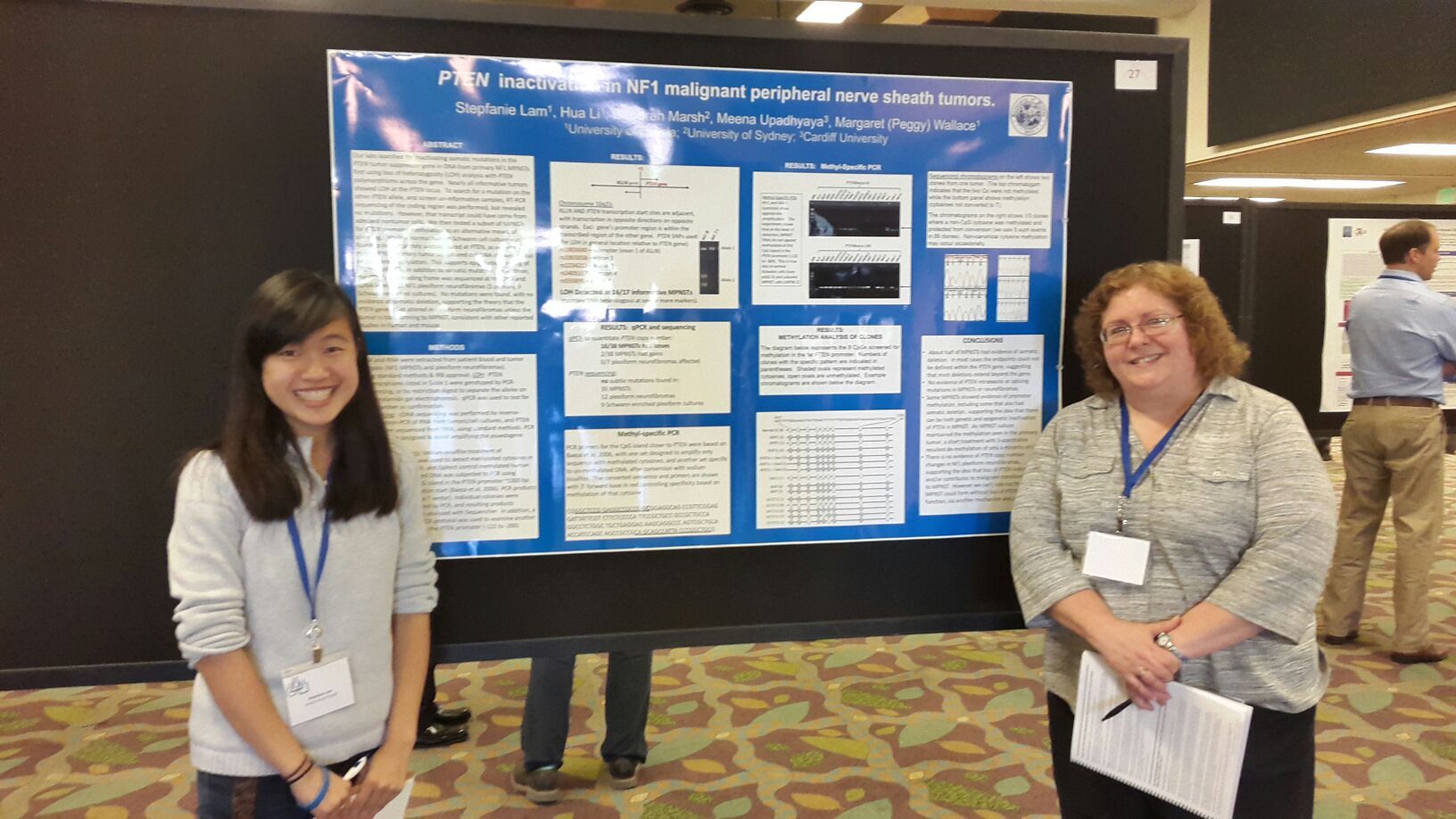

CTF’s funding helped recipients obtain larger grants, leading to a steady stream of exciting discoveries about NF molecular underpinnings and preclinical testing of potential therapies. In 2011, the CTF hired Annette Bakker, PhD, from her position in biotechnology, who as CSO and then President led the foundation to successfully attracting interest in NF from pharma/biotech. From my perspective, NF1 was showing that it was clearly more complicated than we thought and did not want to reveal its secrets easily. We’d set up experiments to test a simple hypothesis using patient samples, and instead of a yes/no answer, the result would be some yes, some no, with no obvious explanation. Heterogeneity everywhere, scientifically and clinically, making simple conclusions impossible. This characteristic slowed progress in therapeutics, but finally Dr. Ratner’s group had a statistically-significant result with a MEK inhibitor in a mouse plexiform neurofibroma model, which led to the first FDA approved drug. However, even that is only a partial breakthrough because not all patients respond or tolerate it, and it is only approved for inoperable plexiforms in kids. A long way to go, but it is heartwarming that many of the clinical trial pioneers are women, such as Brigitte Widemann, whom I remember speaking with at an NF Conference when she was early in her position at the NCI.

At this point, 36 years into studying NF1, it is impossible to keep up with the literature (just in the past year, there have been almost 600 publications about NF1). The NF Conferences have so much content that concurrent sessions are needed and venues that can hold over 500 people. I could never have imagined this degree of progress! However, there is still the sobering reality that a number of my research participants have died of MPNST over the years; there are really no better therapies for this cancer now than 20 years ago. And patients still have no other FDA-approved therapy options. Because finding doctors with NF knowledge was a huge problem, I’ve helped educate our next generation(s) of physicians about NF through patient presentations and lectures to medical students throughout my tenure here at UF. In the face of a current lack of therapies, that is the least I can do to help patients and families find knowledge and support. I have been honored to have collaborated with many labs over the years, sharing knowledge and reagents. I hope that this is helping contribute to development of better therapies. It also honors patient contributions; without the participation of these individuals and family members in NF research efforts (mine and others), progress toward therapies would be lagging well behind. I sense that the field is on the cusp of a breakthrough in therapies (all NFs). I don’t think there will be one answer, but that is OK – having multiple proven therapies will help ensure that at least one can be found to help each patient, so I’m glad that there are multiple entities funding these various research directions. There will no doubt still be surprises to be found (explaining the heterogeneity and/or NF mysteries). These discoveries will transform the field and might even lead to the prevention of serious complications. I look forward to celebrating those days, even though I’ll be formally retired by then. But I’ll be watching. For anyone who wants to reach out contact me at 12peggy@gmail.com.