Serendipity: A Woman in the World of Neurofibromatosis

Rosalie Ferner MD FRCP, Neurofibromatosis Centre, Department of Neurology, Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust London

Discover more articles in the Women in NF series by clicking here.

My journey to the undiscovered country of neurofibromatosis was fortuitous. In the mid-1980s, I was working as a junior neurologist at Guy’s Hospital in London, and I was the only woman in the neurology department. I had taken an unusual and circuitous path to neurology, graduating in modern languages and literature and then training in medicine.

At that time, it was customary for British neurologists to undertake a doctoral thesis (known then as an MD). I was unkeen to embark on the proffered projects: investigation of the neurophysiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome or evaluation of the role of campylobacter in the disease. The exasperated head of department threw down the gauntlet – I could accompany him to an international conference on neurofibromatosis or leave the department of neurology. I accepted with alacrity, thinking of travel to far-flung destinations. In truth, I had encountered only two patients with “von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis” in my training. The first was a man in his sixties with visible neurofibromas and cerebrovascular disease. The second patient was a young father with a peripheral neuropathy and a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, (referred to then as “neurofibrosarcoma”), that metastasised to the lungs and was unresponsive to chemotherapy.

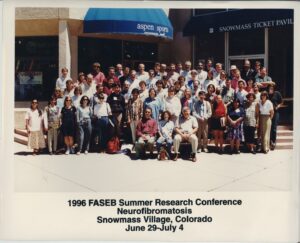

It transpired that there was no journey to exotic places. The 1987 international conference took place in Egham, Surrey; I was accompanied to the door of the Runnymede hotel, exhorted to “have a good conference,” and then left to my own devices. At that time, I was reticent, shy, and out of my depth in a world of genetics. However, I have a clear memory of meeting Dr Susan Huson, already a well-known British geneticist, and Dr Eugen Boltshauser a paediatric neurologist from Zurich. They took time to talk with me and to share their knowledge and passion for working in the emerging field of neurofibromatosis. At an embryonic stage of my career, I understood the importance of approachable experts willing to offer support, transfer skills, and instill enthusiasm in clinicians and scientists entering the world of neurofibromatosis.

In 1987, the NF1 gene had not been cloned and I recall a heated discussion in the conference about the jerky progress in linkage studies. I was impressed that after initial reluctance, the participants agreed to form a consortium that would pool resources to produce an exclusion map and avoid duplication of effort. I glimpsed Dr Riccardi from afar as he rapidly collated the shared data, but I did not have the confidence to introduce myself to him.

I was more engaged in the clinical sessions and recognized the value of meticulous documentation of the clinical features of neurofibromatosis 1 in the South Wales population study. However, it was a talk by Dr Brigitte Samuelsson from Gothenburg on “mental handicap and psychiatry” that fired my enthusiasm. In the early 1980s she had studied 96 individuals with “von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis” living in Sweden and noted a high frequency of psychiatric symptoms and mild cognitive impairment. The cognitive phenotype had not been clearly delineated and there were no published controlled studies. I was hooked!

I embarked on my doctoral thesis to investigate the nature, frequency, and severity of “intellectual impairment” in neurofibromatosis 1. I carried out one of the earliest and largest cognitive studies on both adults and children and their controls. I undertook neurological and psychometric testing on 103 NF1 individuals age 6-75 years and 105 controls, equated for age, gender and socio-economic status. The mean full-scale IQ was significantly lower in than the control group, 88.6 (SD 14.6) compared with 101.6 (SD 14.2). However, the cognitive impairment was mild, and only 8% of NF1 patients had an IQ < 70. The NF1 individuals had significantly poorer reading skills and impaired short-term memory. On a computerized performance test battery of complex tasks, the NF1 group had significantly slower mean reaction times and higher error rates than the controls. Overall, the patients displayed impaired attention and were slow to develop and adapt strategies for complex and unfamiliar tasks. This study highlighted the importance of frontal lobe difficulties in NF1, but in the 1990s, influenced by mouse studies, the prevailing research focus was on the temporal lobe. It took some years before the NF1 world agreed that the frontal lobe was of major significance in the cognitive profile.

Our hospital started using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as an imaging modality in 1988, and I undertook 33 brain MRIs as part of my study. I did not find an association between cognitive impairment and the presence of focal areas of signal intensity (FASI) in the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and brainstem. These changes were known at that time as unidentified bright objects (UBOs) and are generally thought to be due to aberrant myelination.

I recall presenting my early findings at a regional neurology meeting attended by about 50 male neurologists and one other female neurologist. A senior male colleague stood up to congratulate me and said he was impressed that “as a woman,” I had undertaken and discussed MRI studies at an academic meeting! Before publishing the cognitive and MRI study in 1996, I took an a career break and then worked part time – our daughter Francesca was born and it was of paramount importance that I was able to witness her early milestones and watch her grow up.

I recall presenting my early findings at a regional neurology meeting attended by about 50 male neurologists and one other female neurologist. A senior male colleague stood up to congratulate me and said he was impressed that “as a woman,” I had undertaken and discussed MRI studies at an academic meeting! Before publishing the cognitive and MRI study in 1996, I took an a career break and then worked part time – our daughter Francesca was born and it was of paramount importance that I was able to witness her early milestones and watch her grow up.

As I had recruited over a hundred patients to participate in my research study, I offered them clinical care in return for their efforts. Accordingly, I started a monthly clinic in 1996 in the “graveyard slot” of Friday afternoon – an inconvenient time to find anyone to give advice on complex cases. The issue was highlighted when we performed an urgent MRI on an unsteady patient that revealed an aggressive glioma. I experienced the stress of trying to transfer an urgent patient on a Friday evening to a neurosurgical unit when people were leaving for the weekend.

As the clinical service gradually expanded over the next decade, the need to recruit a specialist multi-disciplinary team became more pressing. I started to look after people with neurofibromatosis 2, joining forces with an ENT surgeon, in a cramped cubicle in his department; subsequently people with schwannomatosis were referred to the clinic as the knowledge of this condition expanded.

Commensurate with the requirement for a specialist team was the need for funding. Serendipity again played its part in the development of the service. I recall having a fraught communication about a patient with a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, with a recalcitrant surgeon at another hospital, and I grumbled to a friend. He suggested that I contact the head of rare diseases at NHS England to see if he could assist in solving the problem. This dynamic leading clinician arranged to visit Guy’s Hospital, and I explained my dilemma and vision for the service. The response was to suggest that I apply for national funding for NF1 and NF2 under the umbrella of NHS Rare Diseases. The service would be for “Complex NF1” and for NF2. With input from colleagues in Manchester, we formulated “Complex NF1” as rare or potentially life-threatening problems related to the to the disease, that were either over or under treated by non-specialist services. I suggested that the Manchester team should be the second center for NF1. I was national lead for NF1 and it was apposite for Gareth Evans to be the national lead for the NF2 service; he added Oxford and Cambridge as centres along with London.

We opened the multi-disciplinary “Complex NF1” unit at Guy’s Hospital (with Manchester as the second center) in April 2009. The neurofibromatosis centre commenced to the sound of trumpets, quite literally, as the wonderful Rod Franks, principal trumpeter of the London Symphony Orchestra serenaded us in the hospital atrium. In 2010, the four-centre national NF2 service was instituted, and schwannomatosis patients are now also cared for under the specialist centres.

The aim of the national services is cohesive, lifelong surveillance, education, holistic care, and management of individuals and their families. In the Guy’s Hospital Center, we try to undertake clinics in the neurology department and bring in specialists from other departments and hospitals to work with us in our clinic. Children and adults are seen in the same clinical space so that we can witness the changes in the disease over time, and transition care is made easier as patients are familiar with the environment. Almost like assembling a convivial dinner party, we have slowly recruited adult and pediatric clinicians, including neurologists, oncologists, geneticists, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, neurosurgeons, skull base surgeons, peripheral nerve surgeons and plastic surgeons, neuroradiologists, musculoskeletal radiologists, PET experts, clinical nurse specialists, a physiotherapist, a play specialist, an administrative team and a social worker. There are close links with the Manchester, Oxford, and Cambridge teams, and patients are encouraged to join monthly meetings to give their opinions. When I am in a clinic with a new patient, I am mindful of D Vic Riccardi’s advice “to spend the first twenty minutes just listening;” I learned that this is a difficult skill to acquire and maintain in a busy health service.

I am involved with the UK charity Nerve Tumours UK, where I am both a Trustee and a medical adviser, educating patients and clinicians and encouraging patients to participate in decision-making about their disease. I am proud that Guy’s NF service has served as a template for other international neurofibromatosis departments, and we have hosted clinicians from several other international centers to show our model of care. The clinic has grown from a lonely Friday afternoon slot to 12 clinics per week, undertaken by multiple clinicians.

Providence has promoted a happy international collaboration with the illustrious neurologist David Gutmann and the pediatric expert Robert Listernick. In the late 1990s we were invited to Cold Spring Harbour through the auspices of Francis Collins, the pivotal figure in the world of genetics and neurofibromatosis. The ambitious idea was to come to an agreement on the nomenclature for plexiform neurofibromas. On arrival I was greeted by the biochemist housekeeper; she ascertained that I was unconnected with Dr Watson (the Watson of Watson and Crick), who was staying in the main house and I was directed unceremoniously to stay in the annexe. At dinner in the library, I was introduced to Drs. Gutmann and Listernick, and we discovered that we all had daughters of a similar age and that we all shared an antipathy towards their beloved pet hamsters. Out of this social connection and longstanding friendship, we started a collaboration on optic pathway gliomas, investigating the natural history, co-writing a number of publications, and starting the optic pathway glioma group.

I have always been committed to working in partnership with my patients to give them the best possible care; patient-focused outcome measures are of paramount importance in evaluating care or therapy, particularly with the advent of novel drugs. If a tumor shrinks with novel therapy, but the individual still has pain or disfigurement, then the outcome for that individual is negative, regardless of the imaging improvement.

Rachael Hornigold (an MD student), worked with me and John Golding, an expert in psychology questionnaires, to develop the Impact of NF2 on quality of life (NFTI-QOl). Subsequently, I performed a longitudinal study in four institutions and found that the questionnaire tapped into another dimension of quality of life, apart from genotype and physical assessment by the clinician. The questionnaire has been translated into other languages and used world-wide to evaluate outcomes in NF2 patients. John Golding also helped me and our team develop a patient related outcome measure for NF1, the INFI-Qol, which has been used for evaluation of NF1 patients internationally for treatment outcomes and patient wellbeing.

Ever since I encountered the young father with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST) related to NF1, in the late 1980s, I have wanted to improve the early diagnosis and outcomes for people with this complex and distressing tumour. In the late 1980s, people with NF1 were often diagnosed at a late stage of the disease because developing a lump in the context of NF1 was not considered to be unusual.

A lucky coincidence helped me to contribute to improving the diagnosis of this potentially life-threatening complication. Professor Hughes, now a retired head of neurology, paid a visit to the PET Centre to enquire about doing a PET for a general neurology patient. Whilst he was there, he overheard a conversation between the sarcoma surgeon and his clinical fellow about using 18F-2-fluoro-2-D- deoxyglucose (18FDG) PET to diagnose soft tissue sarcomas. He reported the conversation, and my excitement was palpable; this could potentially be transferable to the world of NF1. A collaboration with the inspirational Michael O’Doherty, a stellar nuclear physician, ensued, and we became the first NF unit to show the utility of 18FDG PET in the diagnosis of MPNST.

We carried out qualitative and semi-quantitative imaging using SUVmax (standard uptake value, reflecting the regional metabolic uptake of glucose) with FDGPET and FDGPET CT. In 2008, we detected 116 lesions in 105 patients aged 5-71 years with symptomatic plexiform neurofibromas, including 80 plexiform neurofibromas, five atypical (ANNUPB) neurofibromas, 29 MPNST, and two other cancers. Biopsy confirmed the findings in 59 tumors, and no MPNST was diagnosed on clinical follow-up of 23 lesions diagnosed as benign on FDG PET and PET CT. FDG PET and PET CT diagnosed NF1-associated tumors with a sensitivity of 0.89 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76-0.96] and a specificity of 0.95 (CI 0.88-0.98). In subsequent studies, we were able to show a significant difference in the mean SUVmax between benign, atypical, and malignant tumors. Since that time, there have been a number of PET studies, but different institutions use different scanners, imaging protocols, and timing of imaging, making it difficult to compare across institutions. The promise of circulating tumor DNA as an early biomarker is a tantalizing prospect.

I have been delighted to share my experience in neurofibromatosis with local, national, and international audiences and to participate in many international meetings, including co-chairing the 2017 CTF meeting with Larry Sherman. I was very pleased to receive the Theodor Schwann Award in 2016 and the European Patients NF Award for my contribution to neurofibromatosis in 2022.

I have come a long way from Egham in Surrey, but have been privilege to meet an outstanding group of clinicians, scientists and patients who have taught me how to listen and to evaluate information. Women are now at the forefront of clinical and basic research on this distressing disease.

I hope in the future that novel therapy will reduce the cosmetic and psychological burden of NF1 and that we will have biomarkers that can diagnose MPNST at a very early stage and avoid untimely death for patients. In the UK we must stand firm against budget cuts for people with rare diseases and ensure that they continue to benefit from lifelong specialist management by experts who have the time and tools to care.